Welcome to the "Making Things Matter" Blog for 2013-2014. As Jean and I observe classrooms and notice trends, I will use this space both to highlight effective instructional practices on the part of our new cohort as well as address recurrent problems or challenges people are facing in the classroom.

One common issue in the classroom involves the usage of video as a teaching tool. Video can be a helpful way to engage students, provide them concrete examples, provide another perspective, and so on. But it can also be a pacifying agent, leaving students disinterested or passive in what should be an engaging, activity-centered classroom. It's important to use video in a way that complements your lesson, rather than dominating it.

1) Select a segment of a video, not a whole video.

Students gain just as little from watching a TED Talk of someone lecturing for an hour as they would from watching you lecture for an hour. Besides--most of the strong discussions you might have in class surrounding a certain video are usually centered on a few specific parts. This is as simple as writing down ahead of time the exact segment on the video's timeline (e.g., from 38:10 to 41:02) that you wish to show students. Heck, you can even copy the YouTube URL so that it opens at exactly that moment--just right click on the video and chose "Copy video URL at this time."

As a rule of thumb, I'd keep videos in class at a length of 6 minutes, tops, with lots of discussion in-between if you use multiple videos. The only exception would be when you show students an example speech video during class (e.g., to have them practice grade-norming). But even then, make sure you pick a video that's reasonably close in length to what they'll have to give in class. Watching a 15 minute TED Talk won't help students prepare for a 5-minute speech!

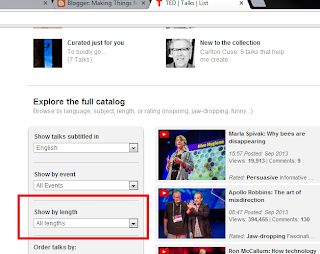

Speaking of which, TED lets you search for videos under a certain length on their web site:

2) Prime students for the video before you play it.

A lot of times, beginning teachers will play students a video without sufficiently priming them beforehand as to what the purpose of the video is--or what they're supposed to be thinking about. There are two problems with doing this.

First of all, video is (or can be) a very passive medium. I'm thinking of back when I was in high school in my sociology class and the teacher played Gandhi to teach us about Indian culture. He spread out a 3-hour movie over an entire week of class time, and didn't really lead into or follow the playing of the movie in 40-minute chunks with any sort of discussion or debrief. Suffice to say, I didn't learn much about Indian culture, other than that they really like salt.

| Image Source: Time Life |

If you don't tell students what to think about with a video, or what to focus on, there's a really good chance they'll just zone out. This comes from years of conditioning from high school teachers who would treat "movie day" as a reward for solving math problems instead of an active part of the learning process. Students aren't conditioned to watch movies or television critically. And if you don't prompt them to do so, or give them a list of questions to think about, they most certainly will not!

Then, afterward, you'll get those blank stares and awkward silences because they haven't been thinking and have nothing to share.

Secondly, passivity notwithstanding, there's the whole matter of interpretation. We're all familiar with those dual weltanshauung photos, where you can see two different things in the same picture. Wittgenstein was particularly enamored with the one where, depending on how you orient it, you'll see duck or a rabbit:

| Image Source: UC Berkeley |

The point is, you can't just show students a video and expect them to see it how you see it. Sometimes students will focus on the wrong elements of a video, honing in on some aspect that is inconsequential to the lesson. Sometimes students will make judgments about a person in a video instead of paying attention to a particular aspect of what they did that you care about (e.g., you might want them to focus on argument--they'll just focus on gestures). And sometimes students will simply stumble confusingly through the video, not knowing what on Earth it is about because you didn't give them any guidance as to why they were watching it, who it features, or how it relates to the lesson.

Let's say, for example, you want to teach students about another culture. In fact, I had a bad experience with this (with high school students who are, of course, tend to be a little more resistant to other cultures than college students). I played them this video of William Kamkwamba, a boy who built a windmill near his family's hut in Africa to generate electricity and gather water:

Because I didn't set up students ahead of time to briefly suspend their cultural stereotypes and assumptions, they didn't focus on the epiphanies I wanted them to about understanding Kamkwamba's cultural situation. Instead, they focused on trivial aspects of his windmill building, whined about his accent and how hard he was to understand, or whatever else.

A better strategy is to tell students ahead of time: "As you watch this video, I want you to be thinking about..." And then provide a list of three or four questions that help students focus on the important aspects of the video you want to draw them toward. Tell them to think about what concepts to apply or moments to feel curious about.

3) Give students a moment to discuss the video with the people around them.

As with other activities and discussions, it's essential after you play a video to give students a few minutes to digest the video on their own. If you jump straight in afterward with a list of questions, there is no chance that a lot of students will have fully formulated their thoughts on the subject yet. Some students need that time--that small-group engagement--to digest the video and voice their opinions on it. Having even just two minutes for students to discuss will go a long way toward getting more of them willing to share out to the whole class.

During this time, I would project on the PowerPoint the list of questions you want them to consider or think about, just to help cue their thinking. If you see a group not talking or sharing, you can walk over to them and simply ask: "What did all of you have to say about the third question?"

4) Think through your debrief ahead of time.

Why are you playing this video?

Seriously--what's the point of the video? Do you want students to model or mimic some behavior in the video? Is there a certain point expressed in the video that matters? Do you want to reinforce a concept from the textbook as it plays out in the context of the video?

Whatever you want to accomplish, you need to map out--in advance--a set of questions or key takeaways that you hope to push students toward afterward. Your questions should push their thinking on the topic, and interrogate them, urging them toward some sort of epiphany or conclusion. If you just randomly ask questions, without having a clear sense of what you want students to understand, chances are that your discussion will not proceed very smoothly or engagingly.

A formula.

Teaching preparation actually can be pretty formulaic. For videos, the process can almost always be:

1) Introduce the video, give some context, and pose some questions/points to consider while watching.

2) Play the video, which should be short but useful as an illustration or point of analysis.

3) Give students two to three minutes to unpack the video with their groups, following questions on the PPT.

4) Lead a full-class discussion, driving them toward a few specific outcomes with your questions.

Hope that helps! Please follow up in comments if you have any further questions, or additional questions for those who want to use video in their lessons.